Jordan Rudess is a familiar name and face to Synthtopia readers, known to many from his work as keyboardist and composer for the progressive rock band Dream Theater, his solo work and his work representing companies like Kurzweil, Korg and ROLI.

Jordan Rudess is a familiar name and face to Synthtopia readers, known to many from his work as keyboardist and composer for the progressive rock band Dream Theater, his solo work and his work representing companies like Kurzweil, Korg and ROLI.

In addition to his musical chops, though, Rudess is also a gearhead and a savvy businessman, and he’s drawn on all these things with Wizdom Music, the company he founded to create the type of software synths that he wanted to play.

This interview is one in a series, produced in collaboration with Darwin Grosse of the Art + Music + Technology podcast, exploring people that are creating new types of electronic music instruments. Previous interviews in this series have included Roger Linn, Geert Bevin and Lippold Haken.

In this interview, Jordan Rudess talks about how he became an electronic musician, his approach to live performance and his vision for the future of electronic music instruments. You can listen to the audio version of the interview below or on the A+M+T site.

Darwin Grosse: How are you doing and what are you up to, Jordan?

Jordan Rudess: I’m doing very well. I’m touring with the Dream Theater right now, floating around the US and having a good time.

Darwin Grosse: Thanks for taking time out of your schedule to talk to me, I really appreciate it. So, in addition to the work with Dream Theater you’ve been doing work as a software developer and working with controller manufacturers. What are the things that are really current for you right now?

Jordan Rudess: At the moment I’ve got my hands in a bunch of different places. As usual. I’m just very passionate about sound and different ways to express sound.

You know for many, many years – basically starting around 30 years ago – I started to get very involved with some of the manufacturers. I worked with Korg for a little while and Kurzweil.

I’ve always had a love not only of playing but of just kind of like getting my hands dirty in the world of how to make sound and what are the best ways to do it. What does technology offer us as musicians and how do you improve on that? And what can you do to make it the best experience?

So these days I’ve been very involved with my company Wizdom Music. Wizdom Music has for quite a few years now been working on cutting edge music apps, primarily for IOS. It got started with MorphWiz and these days I’m working with some people out of the Stanford University CCRMA group and we’re working on a pretty cool musical instrument called GeoShred – so that’s a lot of fun.

We’re working on a very advanced MIDI implementation for both MIDI OUT and MIDI IN that uses the new MPE (Multidimenional Polyphonic Expression) standard. So that keeps me busy, as well as my consulting gigs. Those involve working with ROLI, who are the makers of the Seaboard; CME, who make the Xkey; and a new company I’m starting to work with called MIND Music Labs, which are developing the Sensus guitar.

So my days are basically filled with thinking about the future of musical instruments and this new control, which technology offers in some of these different spaces.

Darwin Grosse: As a player, what is the thing that draws you into these expressive controllers? And – as a really good keyboard player – how does a new keyboard actually help you?

Jordan Rudess: Well, you know all these different technologies offer different things.

I tend to be very flexible with that whole idea. Whether it’s just in playing a weighted 88-note keyboard or playing a keyboard that’s just got smaller keys, the reason I’m flexible is just because over the years I’ve just played them all. You know, everything from a Casio SK1 to my Steinway piano.

I tend to be very forgiving – or just so interested in what they offer, from a musical technology expression point of view, that I’m willing to go for the ride and adjust my technique.

It was a big dream of mine for so many years to be able to work in the area of a fretless instrument as well as a diatonic instrument and how those two worlds were going to be put together. So in dreaming about that, it opened me up to the idea of some of these other physical controls. It started for me with my own MorphWiz on an iPhone.

I was dreaming about how could you use this multi-touch surface to actually control music in a way that you haven’t done before. And the first hardware instrument that I played that offered that was the Haken Continuum.

The Continuum was this multi-dimensional instrument in itself which is kind of a flat surface. I was very open to it – kind of adjusting my technique and trying to understand what would bring these new results.

But it all stemmed out of this desire to work in both the fretless and diatonic domain and figuring out different ways to put them together.

Darwin Grosse: I heard somebody say that every guitar player wishes to have the precision of a keyboard player, and every keyboard player desires to have the sloppy expressiveness of a guitar player. Right?

Jordan Rudess: Yeah.

ROLI Jam with Jordan Rudess, Eren Basbug, Marco Parisi and Elijah Wood on drums:

Darwin Grosse: You have a very expressive way of playing and it seems you can naturally slide into the playing technique that’s necessary to get some of that expressiveness out. Do you have a history playing an instrument other than keyboards?

Jordan Rudess: I did play some guitar growing up. And that I think was very useful to me, because on a guitar it’s such a different kind of an interface, if you will. Especially like a piano keyboard. Where on the piano you can’t bend the pitch at all.

My friend Roger Linn likes to say that a piano keyboard is more like the on and off type switches. You just press them down or you lift them up.

That’s maybe a kind of cold way to think of it. But in reality, and this is coming from somebody who’s gonna be a classical pianist, he’s kind of right.

Not that you can’t make beautiful music on a piano, but it is just on or off and the guitar allows this whole different expression. Where every finger that goes down on a string, you know, you can bend, you can shake … it’s gonna be completely independent, per finger on the string. So it’s a different way of thinking in the very basic form.

Having that experience allowed me to approach whatever instrument and have that in mind. I find people who have never played another instrument besides the piano, when it comes to thinking about doing a vibrato – like actually playing a note and moving your finger on it to try and influence it in a different way – it seems very weird.

Darwin Grosse: Right.

Jordan Rudess: But for me, it’s always been natural.

I like the idea of vibrato. I don’t have a problem putting my finger down on a note – whether it’s on my iPad, my Seaboard, my LinnStrument, my Continuum, whatever – and just kind of like moving and doing my own vibrato. It’s natural. I think it’s a really great thing. So that experience does help.

Darwin Grosse: When did you get started with music? When did music technology get into play for you? And who are some of the people and things that influenced you along the way?

Jordan Rudess: It all started for me back when I was about seven years old, in the second grade and I would go in and just start playing the piano in the classroom and even accompany some kids on the various little songs they would sing.

Jordan Rudess: It all started for me back when I was about seven years old, in the second grade and I would go in and just start playing the piano in the classroom and even accompany some kids on the various little songs they would sing.

One day, the second grade teacher called up my mother and said “Oh, your child is playing the piano so nicely. It’s wonderful to have him do that.” And my mother was like, “What do you mean? We don’t have a piano, he doesn’t play the piano.” And the teacher was like, “Well he does. He plays the piano at school!”

So about a week later there was a piano in my house. My mother decided to buy a little piano and started me on lessons. The lessons started out with this local teacher who would come around with the little … what was it called? The little red book that everyone studies from.

Darwin Grosse: John Thompson?

Jordan Rudess: Yeah, right! And I was playing that, but the teacher realized pretty quickly that I had a good ear and I was combining some chords and doing a little improvisation.

So he abandoned the book and he started to teach me how to find all the different major and minor chords and all the inversions. About a year into that study, I had a family friend who came over and knew a little bit more about music than my parents did and said to my mother, “You know you really need to take Jordan to a serious piano teacher, because he’s got some talent.”

So I ended up studying with a Hungarian woman. Funny enough, her son went to Julliard and he had gone to the college division and he left the college division, because he went off to play in Guy Lombardo’s band. And my teacher, whose name is Magda, who was this very serious classic musician herself, never recovered from having her son leave the Julliard classical world and go join Guy Lombardo’s band.

So when she met me she thought immediately thought, “Okay, this is gonna be my new son and he’s gonna go to Julliard – and he’s gonna stay there!”

So she taught me very seriously. She’d give me little kicks under the table to make sure I was doing the right thing. And she prepared me to go to Julliard.

I spent a little bit over a year with her and then, when I was nine, I actually auditioned for Julliard and I got in. And funny enough, I had to relearn with my teacher Katherine Parker. She wanted to take me back a little bit and start me again with technique, which was actually a really good thing, because my teacher Katherine Parker was the assistant to Rosina Lhevinne, who is probably the most famous piano teacher of the last 100 years.

Darwin Grosse: Right.

Jordan Rudess: So, I’ve always been an improviser, but I started a really serious path in Julliard.

Because I love to improvise, I also love to hear different kinds of music. And I found I had to hide it.

I’d go into the practice rooms at Julliard and just kind of bring my friends and say, “Hey look at this blues thing!” And we’d all smile and laugh, but it was all very private and secret, until I got to be about 16, 17 and two of my friends started to turn me on to Genesis and Yes and ELP.

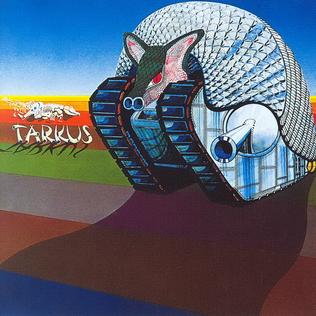

One day, someone brought over the Tarkus album by Emerson, Lake and Palmer and that became something that was really pivotal in my life. I realized just how powerful keyboards could be. I mean, I knew the chords and I knew the rhythms and that wasn’t too new to me. But the sheer power of what could happen from a keyboard really influenced me.

One day, someone brought over the Tarkus album by Emerson, Lake and Palmer and that became something that was really pivotal in my life. I realized just how powerful keyboards could be. I mean, I knew the chords and I knew the rhythms and that wasn’t too new to me. But the sheer power of what could happen from a keyboard really influenced me.

I started to listen to that over and over again and I started to bug my parents about getting a synthesizer and started to post pictures up on my wall of Rick Wakeman, Keith Emerson and Minimoogs and then finally after enough pushing and yelling about it I got a Minimoog.

So I got through the pre-college division of Julliard which, of course, leads up to when you’re ready to go to college and you have to re-audition. At that point, I was kind of thinking I wanted to do something else, but there’s a lot of pressure from teachers and parents and all that kind of good stuff.

So I ended up auditioning for the college. I got in with this sort of high-end teacher and, about a year after that, I decided that that was really it – I didn’t want to do it anymore.

It was the day that I walked in, I had been studying the Chopin G Minor Ballade. I studied it for about a week and I could play it. But I walked into the lesson, I had my music and I sat down to play it. About halfway through the piece, this teacher walks over and she took my music away and I said, “Oh, I need that.” And she said “Well, when you’re studying with me, you need to memorize it.” I said “But it’s a 40-page piece and I’ve only been playing it for a week.”

So I think that might have been my last lesson.

So after that, I got more deeply into my other world. And I didn’t really even know where to go with it. I was interested in sounds and synthesis and, you know I’d heard Tangerine Dream, but I didn’t know how to interface with anybody outside of the Julliard world.

So I was almost like a prim and proper classical musician that was locked in this particular social situation, with elitist kind of people. It really was very, very confusing for me.

So I spent a bunch of years just trying to figure that out and doing different things. Everything from playing in a space band where I was playing Minimoog with a pedal that would take you from below your hearing to above your hearing. You know, custom made that friends did.

To joining a group like Speedway Boulevard trying to … experiencing the whole get involved with a record company and you know all that that involves. And playing in local bands and supporting myself playing in restaurants and bars and all this crazy stuff.

All while being totally into synthesizers and sounds. It finally kind of clicked when I was a little older. When I was about 31 or so I connected with Korg and I got a gig with Vinnie Moore, this really cool electric guitarist. I kind of got into a little bit more of the real world, as far as the musical manufacturers and the music business, with the Mini and Jan Hammer and Tony Williams and all those people.

And then the path really started to change.

Darwin Grosse: From the standpoint of a player, you had a relatively natural growth into playing and eventually ending up working with Dream Theater. In the music instrument world, you just came on like a flash. What is it that you do, or you did, that made people in the music gear industry pay attention to you?

Jordan Rudess: What happened was, when I joined Korg and I was a product specialist, they would have me come to all the different conventions.

Jordan Rudess: What happened was, when I joined Korg and I was a product specialist, they would have me come to all the different conventions.

At all those conventions, I would use those conventions as a vehicle to make music and to play. Korg in those days was really into it. They were into having me organize either a small ensemble of keyboard players or to play by myself and to show off their technology.

What was cool was that, because I was showing off a technology, it wasn’t like a standard keyboard player in the Prog world that would use say a Fender Rhodes for this, a Clavinet for that, and a Hammond Organ for this. My job was to make their technology really sing and to do everything that it could do and show the power of it.

So I would get deep inside these instrument, starting with the Korg M1, and really learn how it worked and do whatever it took to bring out the musical magic and the power of it and then present it in front of other people.

So I would go to these shows and I would put on a musical presentation using these instruments, focusing on the particular instrument that I was assigned to really present.

And then people would cover it, the magazines would all cover it. They’d say oh, this keyboard player Jordan Rudess was a highlight at this year’s NAMM show, because he’s playing this…whatever…and he was showing this instrument.

So people really started to notice me and in connection to the technology. I made a lot of friends through the years within the musical manufacturing world. I knew so many people and they knew me because they’d come and see my demos.

So after Korg I worked for Kurzweil for a while.

Between those two companies, we got very dialed into that part of the scene which was the music business from the manufacturers’ point of view. It also helped to connect me with getting in the door of the world of people who were doing recording and touring and all that kind of stuff.

Darwin Grosse: So I’m curious. Of the stuff that you did in those early days, working with Korg or Kurzweil, what was the instrument that was the hardest one for you to crack?

Jordan Rudess: That’s a good question. I was always working on whatever the latest piece of technology was, and I was kind of lucky, in a way, that when I was working with those companies, I came into them at points when they were doing really innovative things.

People will remember that the M1 was really, at the time, just this amazing breakthrough. It was the first instrument that really presented sampling the way that it did. You had these well developed multi-samples and you could do things that you could never do before.

So it started a path with the companies that every time a new instrument would come out, it would be very excited because it was kind of like taking off from this introduction of the M1.

So I would be showing the M1, which was obviously a joy because it was so different and powerful, and then the M1 led to, I don’t remember the exact order – but the T series and the O1 series, so I just kept watching. It’s almost like you wake up every day with technology and the technology is just … getting better and more fun.

Not to say there weren’t challenges within these instruments. Some of the ones that had more of an impact on me, that might be a good way to look at it, would be something like a Wavestation that all of the sudden changed the game again. The Korg Wavestation was an instrument where you could actually start to have more than a single event under your fingertips at one time. That really got me thinking and also very involved with programming the instrument.

Basically you could put your finger down on a key and you could set up a series of events or wave forms and you could have them just kind of like go into each other right away or you could cross fade and you could tune them and all kinds of good stuff. So when your finger went down on the keyboard, you were controlling multiple events.

So really, really fun stuff. That was an instrument that even to this day is inspiring. Then when I went to Kurzweil, they were working on the K2000. And the K2000 was another instrument that was really, really important. Because, again, it was kind of like breaking down barriers of what was possible on a keyboard instrument. Super powerful.

The engineers and architects at Kurzweil have this vision of technology called VAST, which was basically giving the end user the ability to put any kind of synthesis blocks in whatever order they wanted and the effects were very powerful. It was just getting involved with the next level of technology.

It was challenging for people to wrap their heads around with, especially at first, but well worth it. Actually, I ended up using Kurzweil technology on my first Dream Theater tour. What did I have? Like a K2500 or something like that on some of the first tours.

I’d sit on the side of the stage … almost every show I’d have to sit there, almost up until showtime, because it was so complicated…getting all the samples into these machines. It was very powerful, but it was not friendly at all.

That was ridiculous – I remember sitting on the side of the stage trying to do that. How the whole disk architecture was like, “Whoa, this is crazy!”

These days, of course, I’m working with the Korg Kronos, which is a totally different thing. I don’t have to do that.

Darwin Grosse: We’re talking to you during a stop on your road tour – can you give us an overview of what your road rig looks like now?

Jordan Rudess: Sure. My equipment on the road these days with Dream Theater is in some ways pretty simple. Most of my show is accomplished on a Korg Kronos – the 88-key version.

It handles really 96% of what’s going on in that show, which is pretty crazy, because I’ve always been someone who has opted to use really powerful technology but not the standard kind of Prog Rock keyboardist who uses multiple keyboards. It’s never totally been my thing. I’ve instead chosen to really dig deep inside of these pretty powerful instruments and get the most out of them.

So the Korg Kronos is the main thing and then I also use the ROLI Seaboard, I have a RISE 49 on tour with me and that is connected to an Apple computer to run the Equator software which is the sound for that. In addition to that, I use my own GeoShred App on an iPad Pro. That, plus I have two iPads on the stage with me. One, I use to read some scores and the other iPad is being used as a musical instrument.

That’s my system. And then I’ve got a pretty cool custom stand, which is not the same kind of technology, but it’s pretty cool. It’s got kind of a hydraulic system in it, which can tilt in different ways and move around as well, in a 180°.

Darwin Grosse: You said you sort of steered away from the huge bank of keyboards that’s the prototypical image of a Prog Rock keyboardist. Why did you do that? Was it for simplicity of touring or because it forced you to focus on the instrument? Or just because you found everything you needed in those few systems?

Jordan Rudess: Well, especially these days, I find that something like the Korg Kronos can totally do everything that I need.

As an example, any sound that might not be in it to begin with or that I can’t create using it’s own synthesis, I can sample myself. And that’s what I do.

In the studio, I’ll use any and every toy that my heart desires to experiment or just to build something. And then when it comes to live, I like being very focused in one spot. I can sample anything that I don’t have.

The advantage for that has always been that, instead of having to interrupt a musical phrase by lifting up my hands and jumping to another keyboard, I can be more musical about it and just put things on a quick program change. Especially with an instrument that does not interrupt the sound of the effects every time you do program change.

So I can literally hold, let’s say, a full combination string choir and brass sound switch sounds and be holding that note still and that sound doesn’t get interrupted at all. And the next time I press a key, it’s on the new sound.

So technology like that allows the musicality of my performance from a single controller to be kind of optimized and musical.

The only thing one might say that I’m losing from that at this point might be well it’s not as showy as having the Rick Wakeman type set up, with multiple keyboards all over the place. But I kind of make up for that because I have one of the coolest stands. So I’m not static at all. I’m always moving and there is an element of entertainment that goes along with it that I really enjoy.

So that’s my approach and part of that approach comes from what we were talking about previously which is that, you know, somebody who has a background of being very involved with the manufacturers as a specialist and as a person who could demonstrate these instruments years ago, I tended to get a lot deeper into the instruments than most people would. And also it even went so far as being my role to show how you could get the maximum out of an instrument. In those days there were certain limitations that are not the case today. So today, I’m even happier the way that I choose to do things, because it really flows and ends up being a powerful musical experience.

Darwin Grosse: I have to admit that seeing you in action with that stand is a pretty amazing thing. I think the old bank of keyboards, some of that was just because the flourish of changing keyboards was kind of a statement, but now the kind of thing you can do with that stand is outrageous. I think people can look on YouTube if they haven’t you play it. It’s crazy.

Jordan Rudess: Yeah, it’s really, really fun. That’s my way to have fun and kind of put on a show as well, which I enjoy.

Some people are not so much about that or maybe they’re not as concerned with that, but I feel like in my business, I’m a musician first, but I’m also an entertainer.

I enjoy performing, putting on a show and that kind of fits into my groove pretty nicely.

Darwin Grosse: Now, as you suggested, when you’re in the studio you have the luxury of using anything. People love to have you work with their instruments and so you have no lack of opportunity. How do you choose a favorite instrument in the studio and what are some recent favorites of yours?

Jordan Rudess: Good question. There’s so much software out there these days and it really is a big party when I go into the studio, because I love things that make cool sounds and I definitely have no shortage of cool stuff.

One of my go-to software instruments is Omnisphere, which is a lot of people’s favorite but it’s just so deep and it’s a wonderful program.

I tend to gravitate towards that a lot. Things like … right inside of Logic, which is the DAW of choice for me right now, there’s an application called Alchemy which is also really, really powerful and I love that. I use that a lot as well.

And then for orchestral sounds….there’s a guy named Kurt Ader has a library called KApro and he makes incredibly playable sounds specifically for the Korg Kronos. What’s interesting is that he chooses that as his outlet for his libraries because the Kronos actually does some things that the software is not even doing yet.

Like, within the Kronos you have the ability to have these wave sequences and the ability in that case to have a different wave form up to a really high number. I don’t remember the exact number right, but it’s kind of like a round robin, an extreme round robin idea. Every time you play the note, you’re not getting the same sample, but it can alter and change a little bit, so it becomes very organic.

So his libraries are really beautiful and you know there’s a lot of other things. I use Kontakt and sometimes writing to the factory libraries of that. But I’ve got a lot of different plugins that go with that. The guys at Output are making great stuff and a company called Sample Logic, that I tend to use a lot of their stuff.

And, for piano: I used a Steinway piano on this last album and a Hammond organ, instead of digital pianos. Although, I should say that even on The Astonishing, which is the latest Dream Theater album, there’s still some digital piano, where I didn’t think it was both that necessary to use the Steinway and also where the electronic digital version just kind of cut better and was a sound that worked better for the song. In that case I’ll use Synthogy Ivory. It’s a really spectacular acoustic piano sound so those are some things that stick out.

Darwin Grosse: You also mentioned using GeoShred in your live rig, which points out the fact that, in addition to being a player/performer/entertainer and someone who works in a consulting role with manufacturers, you’re also kind of a manufacturer yourself, in that you design and help develop these iPad applications.

I know MorphWiz and SampleWiz were the two that I saw come out first and this GeoShred is relatively new, right?

Jordan Rudess: That’s right. GeoShred is my newest application.

It’s a project that is ongoing, actually with some people that I met out of Stanford University at the CCRMA labs.

Stanford has one of the most famous electronic music departments in the world, CCRMA, and over the years I always made it a point with whatever technology I was working, on whether it be a Continuum, an Eigenharp or a Seaboard or whatever, I would stop there and talk to the students and the professors and have a great time there. I’ve even done little concert-like presentations with the students there, it’s been always really fun.

But in my travels there, I befriended some of the guys there like Julius Smith and Pat Scandalis and we formed this relationship to work together on some of the technology that’s been floating around Stanford for a while, which is the physical modeling technology.

We kind of decided that combining our two worlds together would be really productive on every level, because those guys have really deep technology and I have the ability to help design what musicians would really find effective. But also to really get it out there and have it be noticed in the really overcrowded, over-saturated world of product.

So we’ve been working on GeoShred for a while. It’s a combination of this deep technology but also it has a really effective playing surface so you can really fly and become a virtuoso on this instrument and do things that you couldn’t do on anything else, which is fun.

And now, most recently, we’re taking an internal instrument right on the iPad and moving it to a complete MIDI implementation and actually creating a new MPE implementation, which is the technology that’s being used with things like the LinnStrument and ROLI Seaboards and those kind of things. So it’s been a really big project.

I was just working on it this morning actually and playing GeoShred from my Seaboard in my hotel room. That’s gonna be delivered before NAMM time 2017 and I’ll probably be at the show and showing that as well.

Darwin Grosse: Hopefully I’ll run into you. So, this interview’s coming about as part of an extended discussion about expressiveness with instruments, and I’m curious to hear how you view expressiveness on an iPad or another glass-faced instrument.

I was involved way back when when the Lemur first came out and it was a big device, right? And a lot of people struggled pressing on a piece of glass and feeling like that was an instrument and could be expressive.

Jordan Rudess: Yeah.

Darwin Grosse: Things have improved certainly with the iPad, but some of it also is user interface design. I remember the first time I saw MorphWhiz in action I was like, ooh there’s a different way to approach touching the instrument, right?

What is it, from your perspective, that allows a piece of glass to become an instrument?

Jordan Rudess: It’s a great question. I worked hard on that, too, because – on the new iPhone you have an element of pressure that does make a difference, but so far on the iPads, we really haven’t seen that yet. I’m sure in the future we will.

Jordan Rudess: It’s a great question. I worked hard on that, too, because – on the new iPhone you have an element of pressure that does make a difference, but so far on the iPads, we really haven’t seen that yet. I’m sure in the future we will.

So there’s a limit to just exactly what your pressing on the glass will do. But that said, there’s so many ways, there’s so many positive things about being able to play on a multi-touch surface like an iPhone or an iPad or any of the multi-touch devices that are out there.

MorphWhiz was my first experiment into that world and it was a very expressive instrument. The reason that it is expressive, even without things like Polyphonic Aftertouch, is because, all of the sudden, you could have this area where you could express a note. Like in MorphWhiz, you had long vertical lines for every note and every note you played was independent. So you could assign the vertical throw of a note to any type of temporal parameter or volume and that created the expression right there.

Plus the fact that each note was completely independent, so as you’re expressing timbre you could also be controlling pitch. So it becomes a little bit more like a guitar or a violin.

In that sense, it’s very different than your standard keyboard, where, if you move your pitch wheel, everything is gonna change. Or if you apply some aftertouch, in general, everything is gonna change as well.

So, even without some additional touch features, like aftertouch, the multi-touch device like an iPad becomes this kind of really expressive musical controller. And there are things you can do. Like, in MorphWhiz what we did was we added the visual element so you’re also combining the idea of visually expressing … as you’re morphing through wave forms you’re also visually affecting and morphing through the visual wave form.

And then, you know, in various apps you try to do different things. Even talking about other people’s apps, there’s ones that where you’re strumming a guitar.

And there’s ones that are really good, where they’re actually almost fooling your brain because when you touch a string you’ll see it vibrate in a really cool way and it’s hard to separate your senses. You say, “Oh my God, okay that’s just visual!”, because sometimes you feel like it’s actually happening.

It’s funny, because, as a developer you can really use the visual sense to influence the way that something feels. Granted, you want more than that, but taking advantage of the fact that you can have that is one of the keys to allowing the user to feel expressive and like they’re getting something out of what they’re doing with the instrument.

Darwin Grosse: Sure.

Jordan Rudess: But beyond that for me, just playing on the glass. If I’m shredding on GeoShred, I like it. You know, just like sliding on the glass and doing all the kinds of cool pitch bends that you can do on it, that you can’t really do anywhere else. It’s awesome!

I always want more but, hey, GeoShred is one of the coolest…. It’s my product, so maybe it sounds too egotistical. But it is one of the coolest ways to shred and bend pitch and become your own Jeff Beck/Steve Vai on an iPad.

Darwin Grosse: Over the course of this series of interviews, I’ve talked to Lippold Haken and Roger Linn and other people who are instrumental in making the instruments of the future But I’m curious, from a player’s standpoint, what do you see or what do you hope for for the future of electronic music instruments?

Jordan Rudess: I’m really excited about people, designers, companies that are thinking in terms of making instruments as connected as possible with who we are as human beings. Using the technology. Using all these advances and what you can do with the computers and the tech and the different kinds of surfaces of touch – to make it so responsive and organic and natural.

There used to be a day way, back when, when people would actually have an argument and say well, electronic music that’s not as organic, that’s not as real, blah blah blah. And coming from a classical background, having gone to Julliard and growing up playing Steinways, I can appreciate that argument to a point.

But now, in 2016, I gotta say that I don’t give any credit to that. With something like a Seaboard, touch is king, because it’s all about developing the technology where everything that you do with your finger on the surface creates expression.

We are at a point now where the technology is allowing the organic nature of expression and human control to be even greater than it ever has been before.

So for me, the future is about that. But it’s also about incorporating more of the senses together, now that we are starting to explore these really high powered devices that we walk around with, like an iPad. But even more so, we think about what’s going on in virtual reality where you’re surrounded by a 360° world, so it’s getting to a point where we can combine the tactile sense and the visual sense and use technology to really bring all that together.

That’s kind of what I’m interested in – putting those worlds together.

Darwin Grosse: Awesome. Jordan I want to thank you so much for taking the time out of your schedule. I hope that the remainder of your tour goes well. Thank you so much for spending time with me.

Jordan Rudess: Absolutely. Thank you for a very interesting chat!

About Darwin Grosse: Darwin Grosse is the host of the Art + Music + Technology podcast, a series of interviews with artists, musicians and developers working the world of electronic music.

About Darwin Grosse: Darwin Grosse is the host of the Art + Music + Technology podcast, a series of interviews with artists, musicians and developers working the world of electronic music.

Darwin is the Director of Education and Customer Services at Cycling ’74 and was involved in the development of Max and Max For Live. He also developed the ArdCore Arduino-based synth module as his Masters Project in 2011, helping to pioneer open source/open hardware development in modular synthesis.

Darwin also has an active music career as a performer, producer/engineer and installation artist.

Additional images: Jordan Rudess, Darko Boehringer, Korg

Great interview!

I had the same type of piano teacher as a kid, but I guess I didn’t get the ‘protege gene’.

I agree!

Excellent interview!

Very good read. Glad for the Wavestation details.

Did you ever notice that most of the classicly trained keyboard players are often the most boring in that they do little to nothing that is out of the box?

Very good interview. I notice the one pic shows JR holding an iPad that’s running SpaceWiz – I don’t think it ever got tons of press, but it’s a fun app to play with – it offers a rather unique way to build up generative sound textures.