Open Source Synthesis – creating and using open source software and open hardware for synthesis – exploded in 2017 and its growth shows no sign of stopping.

Open Source Synthesis – creating and using open source software and open hardware for synthesis – exploded in 2017 and its growth shows no sign of stopping.

This might not have happened, if not for the work of Eurorack designers like Tom Whitwell of Music Thing Modular, who embraced the open source hardware and software approach. Whitwell’s module designs have been adapted by other designers, evolving into new hardware designs and also being translated into software form.

In this interview, one in a series on Open Source Synthesis produced in collaboration with the Art + Music + Technology podcast, Darwin Grosse talks with Tom Whitwell about his background, how he got into creating synth modules and his thoughts on open source synthesis.

You can listen to the audio version of the interview below or on the A+M+T site:

Audio PlayerDarwin Grosse: Okay, today I have the great pleasure of getting to talk to someone whose work I follow very closely. Tell us a little about how you think of yourself and your work?

Tom Whitwell: I’ve been designing electronics for, it must be about five years now. The way I do it is I got into the sort of DIY around Eurorack. I started making guitar pedals first, then got into Eurorack modules.

The thing I wanted to do at the time was really to get these designs out. So I had ideas and wanted to share them, wanted people to be able to make them. So then I started just sharing designs as open source.

The idea originally was that if I published all of the bits and pieces that you needed – the files to make the PCBs, the files for laser cutting panels, the list of components you needed – then people could take that to manufacture themselves. It was the idea of completely distributed manufacturing.

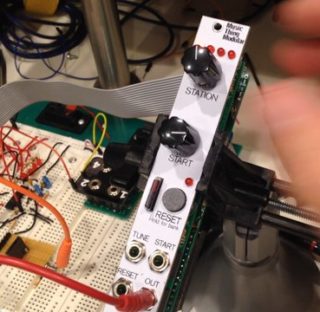

So the first module I did that was called the Turing Machine, which is a kind of random looping sequencer.

I published that and almost immediately Steven Thonk from Brighton, who now runs a business called Thonk, said, “Ah. Well I can help people there. I’ll do a group buy and help people get the components together and organize that stuff.”

So that became a business that sells the modules I design and sells modules that other people design. It’s almost like a hardware record label. I mean I’ve never been on a record label, but I will come up with an idea, I will go to him and say, “You know Steve, I’m thinking about doing this…..”

Generally, he’s then very enthusiastic and says, “Well great. That sounds good. Let’s put some out.” I’ll always be saying, “Are you sure? Do you think anybody’s going to want that?” He’ll say, “Sure, we’ll give it a go.”

Then he organizes the manufacture of making the kits and he does a lot of the customer service….and deals with all the shipping, all of that stuff.

I suppose I’m just like anyone, I’m trying to do something that’s new and that is something that I want to buy that I can’t buy anywhere else. So, if it’s something that I can buy already, I’m not usually very interested in doing it, because I’d rather just buy it.

But if there’s something I can see to add and it may be a small twist or a big twist, then I’ll want to make it. Hopefully it’ll be something that other people want to use. One of the things that’s been really interesting and gratifying is sometimes seeing how modules get used in very different ways from how I might think initially.

So you put something out into the world and you see what people are doing with it, that’s very, very rewarding. My stuff is all open sourced so that means people, I think, are sometimes more empowered to do that.

So people are empowered to write different firmware for modules that have code in them. They’re empowered to make different face plates and put modules together in different ways. Sometimes people will take elements of things I’ve designed and turn them into other things that are exciting.

For me, that’s often the most rewarding thing is just seeing how people make something of the things that I’ve put out there.

Darwin Grosse: You mentioned that you’re sometimes surprised seeing how people utilize your work. What’s an example of something that you didn’t expect?

Tom Whitwell: The best example of that was the Mikrophonie.

I had the idea that you could put a contact microphone and a little pre-amp into a module. It’s almost just like a conceptual joke. I thought it would be fun that your modular would be reactive and every time you flipped a switch or turned a knob you’d be able to hear it.

My thinking didn’t really go much beyond that.

Then once I designed it, I could see people sort of quite liked the idea and it had the advantages that it was really cheap and really easy to make. It became a real sort of gateway thing into getting into DIY. It was very nice as an answer if somebody says, “What should I do first?”

It costs like 30 pounds or something and…..we give very, very little customer support on it, because there’s not very much to go wrong. It’s a proper kit. It’s got proper stuff in it. It’s not some sort of massive thing you’ve got to screw together. It is a real proper way of learning how to do it.

What then happened was when Olivier Gillet at Mutable Instruments came out with things like Rings, and I think it was probably Elements as well. They were doing Karplus-Strong (a type of physical modeling synthesis) with very, very short chain delay lines. People discovered that if you sort of stimulated that with the Mikrophonie module, with the contact mic, you could do this amazing, almost sort of strumming. You could run a platform across the grooves and wedges that are put into the panel. You could be playing it with different textured things, like with the rubber on the end of a pencil, that sort of thing.

It was this amazing, really interesting, nice effect that I never thought of…and was much more musically interesting than what I’d come up with.

So it was really, really pleasing and interesting to see that.

Then the follow up was great as well and Olivier got in touch and said that he liked this effect, he wanted to do a version of the module. His stuff is all open source, my stuff’s all open source, we have the same license.

So the answer was obviously “You can do whatever you like.” I was probably flattered because he’s somebody whose work I’ve followed since he was writing Palm Pilot software.

Then it was a real privilege to actually see his process from the other side. I mean, the level of detail and commitment that he put into what was really a quite simple, straightforward module by his standards, was amazing. I mean, he added a whole bunch of extra functionality that wasn’t in my version. He completely redesigned it and then explained to me what I’d got wrong in my version. He put it out and then he did it with Thonk, a kind of initial run that all went through Thonk so we got the money out of it as well.

It was just a really positive, pleasing experience, that whole thing. Just saying I did something because it was simple and interesting and other people took that and made something cleverer out of it than I could have imagined. It was a very, very positive experience all around for me.

Darwin Grosse: Well you also ended up having your own stuff. Because isn’t the chord module basically just alternative firmware for the Radio Music module?

Tom Whitwell: Absolutely, yeah. So the Radio Music is the only sort of digital module that I have.

I don’t really enjoy programming very much. I mean, I will do it if I have to, because I want to make something work, but I see so many people around here who are so much better at it than I am. And they do it properly and they understand it. Whereas, for me, I really wanted to make the Radio Music, which is this very simple song player that plays back audio from SD cards, and I had a really clear idea what I wanted that to do and how I wanted it to work. That was just within the limits of my coding skills, so I was able to create that.

That again, was a popular module and that it was very much built on other things. It was built on a platform called Teensy, which is a really well-maintained and documented audio library. So it makes it very easy for somebody with limited programming skills to make something interesting from it.

Because it was all built on that platform, it means there’s quite a lot of different thing that you can do with it. Almost immediately people started experimenting with this. Doing different kinds of firmware for it.

I then, I think a year or so after doing the Radio Music initially, had this idea in the back of my head about a module that would play chords. A module that was, again, just a really simple way of getting chords into a module, which is quite a fiddly….

I’ve had modules that are supposed to put out CV for chords and I just didn’t have the patience to sit there tuning oscillators to try and do this.

(Chord Organ) would slosh out nice, interesting chords and a few other shapes. That’s exactly what I designed.

I showed it to Steve at Thonk and said, “I’ve done this. I’m going to put it out as a firmware that people can download.” He was like, “Well, you know we should think about doing some extra panels for it and if people want the software, it goes to a new panel.”

Again, it was really surprising to see how well that was received. People immediately understood that and I think quite a lot of people thought, “Well I’ve got a Radio Music and I use that a lot, actually this sounds good.” And then buy a second one to try it out.

I think I was very keen that we made sure it still remained completely open. So if you’ve got one, you can just download the firmware and give it a go. There was no suggestion of this is something you have to pay extra for if you’ve got the first one.

That was, again, just kind of something that I wanted. It’s the simplest way you can get to the solution that will do that for you, I suppose.

Darwin Grosse: You actually surprise me when you say that you’re not a code guy and you don’t enjoy doing code because, a lot of what I’ve interacted with you virtually has been through code-related items

I mean, whether it’s the Radio Music and then the alternative stuff for the Chord Organ, or you did this cool blog post a while back called, “How I recorded an album in an evening with a lunchbox modular and a python script.”

I read that and I got activated and I ended up doing a version of that that used React to do it all in a webpage.

Tom Whitwell: That’s because you can do it properly. That’s the thing.

Darwin Grosse: Well, but doing it properly is a lot different than having the idea to do it at all.

Tom Whitwell: There are obviously things that you can do with code that are useful and interesting. I enjoy that sort of first bit, of going from having nothing to having something that kind of works.

I’m very aware of the difference between that, and something that is properly shippable and maintainable and efficient. I think as well….there are fewer people who are able to design and route circuit boards than there are able to write code.

I’m definitely better, I think, at making boards and designing that stuff. There’s something I really enjoy about the analog stuff – it’s sort of finished and it resists feature creep. That’s the thing I always find very difficult with software is that constant thought of, “Oh maybe it can do this or that.”

I sort of like the fact that with the Turing Machine sequencer – because it doesn’t have any code in it, it has just these logic chips in it – there’s a really obvious feature missing from that, which is a kind of reset. Which is a feature that sequencers normally have and is useful, but there’s no non-crazy way of implementing reset that I know of or that anyone’s ever suggested in that kind of hardware.

So somebody says, “Well you should put reset in.” You say, “Well yes, but it’s not actually possible. There’s not an obvious way of doing it.”

Darwin Grosse: Is that because this is based off of shift registers?

Tom Whitwell: Yeah. I mean, you’d have to, I think, somehow copy the contents of the shift register back a certain number of steps. I mean, I’m sure you could do it but it just seems silly.

Darwin Grosse: it’s interesting to me that shift registers have been coming up a lot lately. I just got done interviewing Rob Hordyke recently. His bungler circuit is all a shift register based thing.

I didn’t realize the Turing Machine was actually the first module that you had developed.

Tom Whitwell: It was the first module I put out.

Before then, I’d done a few DIY things. I did a spring lever and I think I did the Radio. I had made an initial FM radio module.

But,the first one….I published and put out into the world was the Turing Machine.

Darwin Grosse: How did you get into electronics? Let me ask this first, do you have a day job or is this your gig?

Tom Whitwell: My day job is I’m an innovation consultant, I guess, or sort of product development consultant. My background is in journalism. I did journalism post graduate. I worked in magazines, I was editor of Mix Mag, which was a dance music magazine.

In sort of 1990 to 2002, I was deputy editor of The Face, which was a fashion/style magazine. Then I went to work for The Times – I was kind of head of digital for The Times of London. I was there for about seven years.

So that’s my real background – in writing and, then more recently, moving into digital and product development and that sort of thing.

In 2004, I think, set up this blog called Music Thing, which was about music gear with a sort of … I suppose it was a reaction to the way people often talk about music gear, which is taking it extremely seriously and this idea that if you buy a particular piece of kit then you will be able to make wonderful, particular kind of music with it.

Particularly that kind of idea of you need this piece of kit because it’s got this sound. That’s the thing you’re buying. I always thought that was not particularly credible.

I think people were buying a lot of things because they wanted them and that was why I wanted stuff and it was around the time that all of the VST stuff was becoming very dominant.

I thought, “Well actually, if you’re really into sound, then you can probably do it in a computer and that will be a very good way to make something that sounds great.” And you would see people doing that. Particularly also if you were doing experimental stuff.

Again, with computer you get a lot further with MAX than you might with a lot of things.

I was still really interested in the physical music stuff and so Music Thing was a blog about the love of weird music stuff. Old things and new stuff that was coming out.

So I did that for about four or five years. it did seem to become quite popular. People liked it. I still meet people who remember it.

Then, my day job became slightly more pressing and it was at The Times, so I gave (the blog) up after about 2009, 2010 I think.

Then around that time I think I was beginning to get into things like Arduino. I’ve just always been kind of interested in electronics, but I’ve never known anything about it or never really done any of it.

So, Arduino was the first thing that got me looking at components and bread boards and that sort of thing. I designed a few or made a few guitar peddles from kits and things. So I started getting into from that angle.

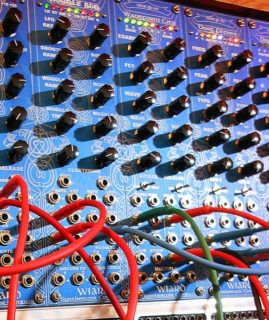

Then, I think one of the things that attracted me to the Euro stuff was just thinking, “Well actually there’s quite an interesting thing to be done here, in terms of making stuff.”

It’s a very easy platform to design things on because you’ve got the power and stuff and the formats are quite straightforward, so you really just need a panel and a couple of circuit boards to create something interesting.

There is such an opportunity to do different things, compared with something like guitar pedals, where if you’re not making a distortion and a delay and a chorus, it’s pretty hard going.

I think the measure stuff just seemed a really exciting, open place and it was around the time that Make Noise was getting started. Their sort of weird, sort of ‘Grant Richter‘ stuff was coming out. It just seemed like an interesting thing to try. So I really taught myself how to do it by reading books like Nicolas Collins Handmade Electronic Music.

It was really that sort of thing and the old Electro-Music forum that were a really good place to learn electronics.. That was how I really got into it.

Then you just go from one thing to the next and next. You think, “Well, I’d quite like to make a circuit board for this.” Once you’ve mastered making circuit boards, the thing becomes repeatable and sharable and sort of publishable. It becomes a thing that people can make.

To some extent, it was a bit similar to the way blogging happened in the mid-90s. My background is in magazines, so if I, in 2004, wanted to write sort a magazine about weird music gear, I would have needed a million pounds and the backing of a decent sized publishing company. It would have sold 20,000 copies and nobody outside the UK would ever find it and it would have just been this enormous fad.

Then blogging came along and you could say, “Well, why I don’t I just have a go at this and see what happens?” And I was able to reach this audience.

By 2012, I was beginning to see that, with access to Chinese manufacturing – being able to get circuit boards printed very, very cheaply in small numbers – there was something that was possible to do there and that could be opened up, in the way that blogging opened up publishing to a much bigger audience.

Darwin Grosse: Going back to this idea of blogging sort of democratizing publishing, there was another thing that happened, which is all of a sudden people found out that they weren’t the only weird person that loved this stuff.

Tom Whitwell: Yeah.

Darwin Grosse: I started getting into modular stuff myself in the mid-90s, and I remember people would look at my stuff and be like “Why on Earth would you want to do that? There are so many better and more interesting things to do in my digital synth, why would I ever want to do such a thing as that, right?”

And so I felt like, “There’s nobody else that likes this stuff.”

Then I ran into Grant Richter and he and I just started doing stuff together. That was neat to have one other person.

But it wasn’t until the Internet lit up and we could start these little forums and stuff that, all of a sudden, you find out there’s 1,000 people or there’s 2,000 people that are into this.

Tom Whitwell: That was exactly the experience of doing the Music Thing blog. It was just “I will write the most obscure and self indulgent thing I can.” And there is an audience for that

I don’t think that’s aberration in terms of journalism. The best magazines, the most successful magazines, were the ones that had….a kind of vision that was self indulgent. It was committed and it was exciting.

I remember reading, when the Beastie Boys published their magazine Grand Royal in the 90s, it was just an amazing thing to see people taking the idea and going with it. They had the money, they were doing it in the platform of a printed magazine, but it was a kind of precursor, of lots of the good things that have come out of Internet culture.

Darwin Grosse: It’s interesting that you got into this from the text side and all that. How did you even have time, let alone the background, to not only learn and embrace the electronic side but also why music? Why not drones or model airplanes or something?

Tom Whitwell: I don’t know. I’d always loved music and I’ve never felt I’m particular useful at making it. But I’ve seen other things that I can do that I’m better at than an average person. Writing articles, probably.

I’m now better than the average person at making circuit boards. I’m not really better than an average guitarist at playing the guitar, as much as I would like to be! But it’s a case of finding the things that you’re able to get good at, I suppose.

In terms of the time, I suppose I just go to bed quite late!

Darwin Grosse: There you go.

Tom Whitwell: I’ve always had hobbies that are absorbing, I suppose. Alongside jobs that are quite demanding.

If you’ve got a demanding job, then having an engaging hobby can be quite a useful release.

Darwin Grosse: That’s a great point.

If you don’t consider yourself a musician, to what extent was the Turing Machine, in sort of it’s semi-random, generative kind of thing, your way of saying, “Let’s get the machines to help out?”

Tom Whitwell: It was exactly that.

I remember I’d got a (Make Noise) Pressure Points sequencer, which is a really nice sequencer. But I realized that what I did with it was set the knobs to random positions and then let it play and listen to it and then maybe moved one a bit. This sounded like Steve Reich or Philip Glass, a bit.

I thought, “Well it’s not right having a thing that you can set precisely and then not sitting it precisely – just setting it randomly.” It didn’t seem conceptually sound really. I thought, “Well is there a way of creating something that does that automatically?”

It was looking, then, at all of the other things that have come along – all of those shift register sequencers, whether it’s the Triadex Muse that Marvin Minsky did or the Buchla 266, which was a similar shift register thing. Grant Richter’s Wogglebug and Noise Ring are similar sort of things.

So there were all these kind of systems using shift registers to make random sequences. I was just kind of experimenting with those circuits and trying to see how to get them to do what I wanted them to do. It was just trying to get something that would loop and would slip…

Darwin Grosse: I think that one of the things that’s really interesting about shift register based sequencers is they seem to tickle the brain in a useful way, right?

Tom Whitwell: Yeah.

Darwin Grosse: Because there’s patterning but it’s not completely repetitive. It’s generative but you can still grasp kind of a sense of what’s going on. It almost seems like there’s a thought pattern behind it.

Tom Whitwell: Yeah. After doing that, I did some experiments with just creating patterns from an Arduino, and then triggering one of those electric, acoustic-sounding pianos from it.

It was really interesting, the very first thing I did was I set it to create random (sequences). Like, “Pick a scale, pick 16 notes, give them random velocities and play them over and over again.”

I was amazed that when you plugged that into a piano, it sounds quite a lot like one of those Spotify, ambient chill playlists. And I don’t mean that to insult the people who make those Spotify ambient sort of playlists, because I did this and I thought, “Well that’s quite interesting.”

Then I set it so it would just change the notes every couple of bars and that sounded really good. That was interesting.

Then, I got into putting Markov Chains into it and trying to make it more sophisticated. But it just became less and less interesting.

I was really struck by this thing. The magic is keys. Having things in key is quite a clever invention, and just repetition. Certainly for me, I remembered a story where Brian Eno wandered around Marble Arch in Hyde Park with a tape recorder running and recorded just random street sounds for three minutes. Then he played it back to himself over and over again and he kind of learnt it so he knew, “Oh okay, this bit’s coming up. The newspaper seller’s going to walk past.”

Once he’d learnt it and remembered it, it became very credible music.

So I do think there’s something about repetition that is just absolutely critical. I just wonder whether you can get a very long way into music that is pleasant to listen to with really, really simple things to generate sequences and repetition.

To some extent that’s a little bit disappointing. You think, “There surely should be a bit more to it than that,” but at the same time it is interesting. That whole experience of when you listen to an album the first time and you don’t really get it. Then, 15 years later, you listen to it and you just know it like nothing else. And it has an incredible emotional impact on you that it wouldn’t have had the first time you listened to it because you haven’t learnt it. You haven’t absorbed it and you haven’t had that repetition.

So, there’s something really interesting there about how music works, I suppose.

Darwin Grosse: That makes me curious, what kind of music do you listen to?

Tom Whitwell: I’m not listening to the latest trance remixes, but I like electronic music like that. I like chunks of folk music. I listen to a lot of music.

Getting into modular and that has been just encouraging me to get a much broader taste, I suppose. Because you get interested in the stuff and you think, “Well, what music is made with this?” So you seek out people like Morton Subotnick or the early electronic music and then you’re in quite a different world from what is sort of ‘normal music’.

I remember reading Alex Ross’s The Rest is Noise, his history of 20th century music. It’s an amazing book and I think reading that, I just got completely opened up into a world of music that’s interesting to listen to and interesting to read about. People like John Cage, who I could read about all day long, I’m not really going to listen to a great deal of his music but there are bits of it I listen to.

I am fascinated by that world and I’m fascinated by people like La Monte Young. I was able to see him playing when I was in New York for Machines and Music.

Just the sort of density of stories and history and kind of creating new things in that history of 20th century music, I think, is amazing.

I could listen to people like Steve Right and Phillip Glass all day long.

I read quite a lot about music, so I was reading a great book called Electric Eden, which is a history of folk music in Britain. So suddenly I’m then listening to Fairport Convention records, which is obviously different than what I was listening to before.

So I do listen to just a lot of different things.

Darwin Grosse: The other thing I really wanted to talk to you a little bit about, because I know it’s important to you, is the idea of the open source and the open hardware community.

It’s kind of neat that this is a thing that the modular world has really embraced. There are a lot of people that I know that have limited themselves to DIY stuff that is based off of open circuits, open hardware, or if it’s digital based, then open software too.

‘m curious why initially you decided to go that way? Because, in the early days, it would have been really easy to say, “Hey I can start a company doing this.”

I’ll never forget, when I interviewed Paul Schreiber (of Synthesis Technology), he was like, “Well hey, if I start selling modules I might be able to buy a new stereo.”

That was his motivation to get into it. How is that you didn’t decide to sell modules and get a new stereo?

Tom Whitwell: I don’t know. I think I came into electronics through the maker movement. Through things like Arduino, so (open source) always seemed like the normal thing to do.

When I started, I had this idea of just saying “Is there a way of getting this out and publishing it to people?” It was almost like a hard way of blogging. And, to do that, you obviously needed to make the designs open.

One of the really interesting things that I didn’t really think of at the beginning was just the discipline of having to show you’re working is really interesting. If you’re somebody who’s not an electrical engineer at all – that thing of actually saying, “I’m going to design this and I’m going to publish it so people can see it.”

The other side of this is if I’ve messed this up, somebody can suggest how to improve it. I think that was part of the thinking when I started and that’s been quite true. It does mean that you can put something out and other people can say, “Well, you could do it like this.” That does happen sometimes.

I’s difficult to say, because it’s something that I’ve done and it would just seem a bit strange to do it any other way.

What came along later was seeing how Olivier did exactly the same thing as me, with the same license. And, you know, there was a sort of journey on that.

To some extent it’s not right to say somebody’s taking advantage of it, but I think it was a case where somebody would say, “Can I do this?” And you would say, “Well, I’d kind of rather you didn’t.” They would say, “Well I’m going to do it anyway.” You go, “Well okay. You can do that. As I said, I would much rather you didn’t.”

For me, all of those cases have gone away. There’s nothing at the moment that I’m looking at and going, “Wow, I’m really annoyed that somebody is doing this thing and I don’t want them to.”

Darwin Grosse: It does seem like that’s one of the things that could be a hazard. Just because you’re trying to make it open and freely available doesn’t mean that other people aren’t going to try and capture commercial market from it and maybe not in a great way.

Tom Whitwell: The thing is, we are capturing a commercial market from it. I think Thonk have probably sold 2,000 to 3,000 Turing Machine kits or circuit boards. That’s a really big, chunky amount.

So, it’s not like we’re not creating a product people can buy. I think that’s where for me it got annoying if somebody said, “Well I’m going to make these really cheaply, because I don’t have any costs and I’m not going to do customer service and I’m not going to add any value to it.” Through Thonk, we’re selling these things and we’re selling at this price because we’re employing people, we’re doing it nicely and we’re making a profit. For somebody to come along and say, “Right. I’m just going to do this stuff super cheap,” it was kind of annoying.

Equally, I’ve had conversations with those people and they’ve said, “Fine. I don’t want to do that. I’m not trying to be bad about this.” I think the community, has resolved itself.

You know, I talk to people about it. They’re saying, “You publish your stuff, then Behringer can come along and make a ripoff of your thing.” You’re just like, “It would take a Behringer engineer 90 seconds to rip off any of my machines.” Then it would take them two weeks to do an amazing job of working out how to manufacture it at the right price in China and that’s what they’d do. They would do that to anyone in the world. The fact that they can see my schematics and have a laugh at them is neither here nor there.

There was something I was reading the other day that was Adafuit, who obviously started a lot of this stuff. And, when Limor Fried did the original 303 clone, the x0xb0x, she did it as open source. I think she said that their license isn’t so much a legal thing as it’s “These are the people I want to hang out with.”

Darwin Grosse: Yeah.

Tom Whitwell: And, to some extent, it’s that. It’s not to say that if somebody doesn’t want to do it open, that’s not fine as well.

Now, you’re starting to see the amount of learning that that community’s got and the amount of ambition. Just a whole bunch of people learning really quite sophisticated electronics manufacturing and then learning how it works.

And I will use Olivier’s module, while I’m trying to figure out how to do this, and you’ll go and look at his module and say, “Oh okay. That’s probably a sensible way of doing it.”

Befaco has a fantastic modular meetup in Barcelona, and there were people there who were saying, “I’ve seen your circuits and I’ve seen bits of your code, and bits of your code are in this module I’ve made.” That’s another really rewarding part of the process. Me sitting there and saying, “I’ve designed these things and I’m not going to tell you what it does,” just wouldn’t give you that.

Darwin Grosse: Before I let you go, what kind of things do you have on the workbench right now that you’re working on? Or what are some areas at least that you’re finding interesting?

Tom Whitwell: At the moment, the main thing that I’m trying to finish off is a module I showed at Superbooth last year, which is called Startup. It is really, really small – 4 HP. It’s a mixer and a headphone amp and a sort of tap LFO.

This was very much that idea of these really small modular, so they’re little lunchbox modulars. The kind of thing you need for them actually to be portable is a nice headphone amp that sounds good. Somewhere for mixing a few signals together. I wanted some kind of stereo spread, because I like stereo in things. Then some kind of a clock normally if you’re trying to get things going.

So, before going to Loop last year, I made a little prototype headphone amp along these lines that was just really, really nice to have in a hotel room and just a little modular to carry around. So it was very nice for that, just being in your headphones doing something quietly with sort of ‘smaller sounds’.

So, I did a prototype of it at Superbooth that was not very good. It kind of worked but not quite right. So I’ve been fixing that, learning how mixers work properly, rather than what I did. And so that’s sort of finishing off and going out to prototype.

Then I’m looking at some sort of small standalone things. They aren’t some big desktop things but seeing things that you can do with batteries and things that you can carry about a bit.

Darwin Grosse: Well Tom, I want to thank you so much for taking the time to talk. It was a lot of fun and I feel like I know a lot more about you and your perspectives than I did before.

Tom Whitwell: Thank you.

Darwin Grosse is the host of the Art + Music + Technology podcast, a series of interviews with artists, musicians and developers working the world of electronic music.

Darwin is the Director of Education and Customer Services at Cycling ’74 and was involved in the development of Max and Max For Live. He also developed the ArdCore Arduino-based synth module as his Masters Project in 2011, helping to pioneer open source/open hardware development in modular synthesis.

Darwin also has an active music career as a performer, producer/engineer and installation artist.

Additional images: Tom Whitwell. Video: brandon logic

Great interview! Tom is already a legend in the modular world!